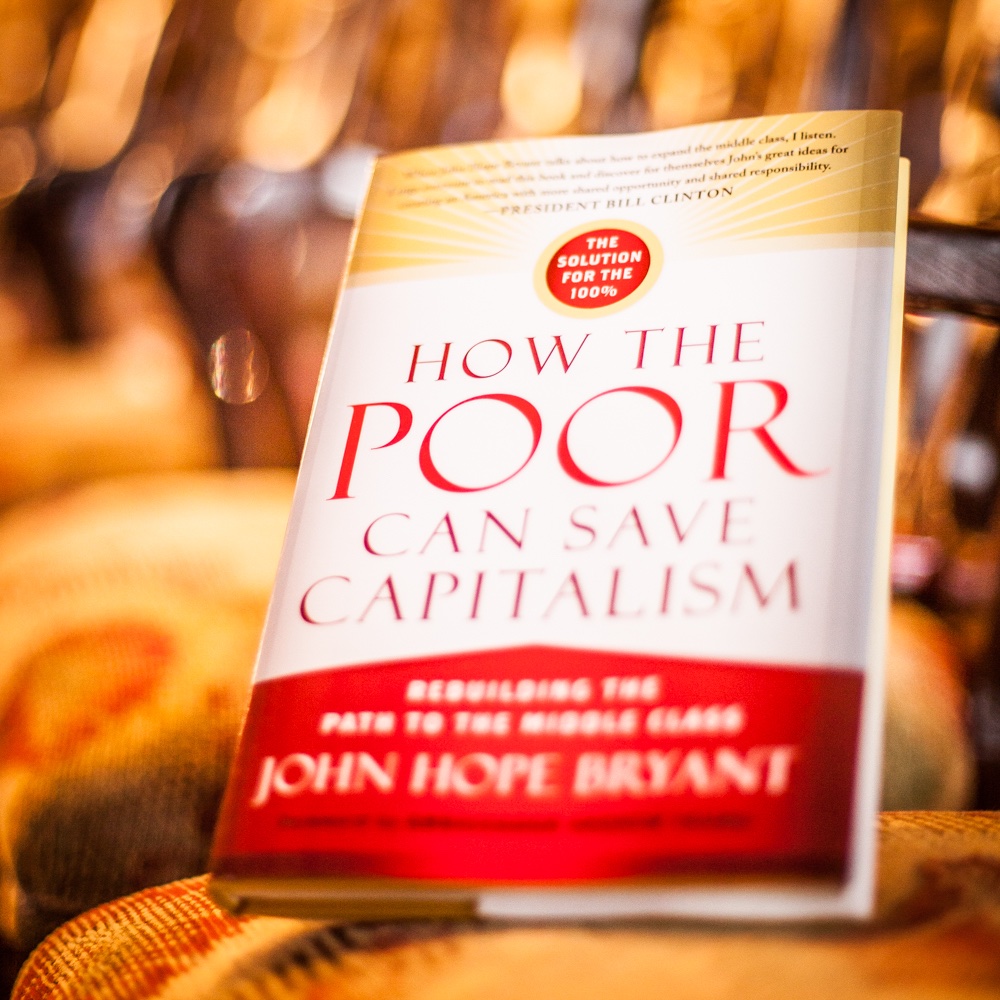

When I sat down with my editor Neal Maillet at Berrett-Koehler Publishing in San Francisco in late 2013, to frame out the vision for what would later become the bestseller “How The Poor Can Save Capitalism: Rebuilding the Path to the Middle Class. A Solution for the 100%,” I had no idea of its impact on the eventual history telling in and of our great nation.

“How The Poor Can Save Capitalism” came out in June, 2014, and was immediately embraced as a national bestseller on several platforms. Not only is the book a sustained bestseller to this day, it is the only bestselling book on economics by an African-American author in the world today.

It has subsequently been translated into 5 languages, and will next come out in Portuegese, in Brazil.

In the book, which speaks to the power of bottoms-up economic growth, and articulates with both stories and facts the ‘rise of wealth from, through and often by the poor,’ I also tell the story of the Freedman’s Bank. This is a story that has been largely lost to history.

The Freedman’s Bank was created by President Abraham Lincoln following the civil war to ‘teach freed slaves about money.’ To bring former slaves into the economy, and to expose them to the power of their own aspirational opportunity. In this case, helping themselves was also helping the rebirth of an America ‘for all.’ The original vision for the Freedman’s Bank was the brainchild of Rev. John W. Alvord of New York.

President Lincoln is rightly so given great credit for seeing the wisdom of this idea of a ‘Freedman’s Bank’ and signing it into law, as part of the larger Freedman’s Bureau, on March 3rd, 1865.

Unfortunately, President Lincoln was assassinated 5 weeks later, and the bank drifted into the hands of individuals with motives other than the uplift of former African-American slaves.

Abolitionist and businessman Frederick Douglass thought this bank so important that he signed on to run it himself, even investing $10,000 of his own money in the bank at the time (this would be approximately $20M today). Unfortunately, it was too little, too late, and Douglass later petitioned Congress to close the bank.

Basically, this bank was the forerunner of modern day ‘financial literacy for all’ efforts at the national policy and partnership level, and it is instructive for our leaders today that President Lincoln thought this important enough to create a bank focused on teaching former slaves about money.

Reading about the fiscal and financial illiteracy problems and challenges of uncompensated former slaves, turned compensated union soldiers of that day, is like reading the chronicles of blacks and other low wealth individuals today — gamed and taken advantage of by payday lenders and financial predators.

In an effort to bring positive attention to this critically important lost piece of American (financial and African-American) history, the organization I founded, Operation HOPE, embarked upon a Freedman’s Bank Tour in early 2015.

The Tour kicked off on March 3rd, 2015, 150th anniversary of the Freedman’s Bank, at the National Archives where Freedman’s Bank records are kept to this day.

We also sent a formal and respectful letter around this time to our own government, respectfully requesting that they consider ‘renaming the Treasury Annex (the headquarters for the Freedman’s Bank) to the Freedman’s Bank Building.’

Nothing much happened with this special request ~ until it ended up on the desk of the right leader. His name is Jack Lew. As in US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew.

Encouraged by this, I subsequently met with Secretary Lew, along with key aides of Lew’s including Wally Adeyamo, Amias Moore Gerety and Melissa Koide, along with my domestic policy advisor Jena Roscoe. I can say without hesitation, that Secretary Lew immediately saw the relevancy, the historic significance, and the possibility of ‘making a historical wrong, right.’

Without this man and his courage to do the right thing, none of the magic that follows ~ would have ever happened. Read on.

I was told by almost everyone that renaming a building was ‘a virtual impossibility,’ but fortunately for me and the nation, Secretary Lew decided to trade in facts instead of cynicism. This is what real leaders do.

Ultimately, I was told that the lawyers cleared the way for the Secretary to make this historic course correction, agreeing on January 7th, 2016, to rename the Treasury Annex Building — The Freedman’s Bank Building.

Who knew, that a simple meeting with a book editor, and the subsequent publishing of a book that many doubted was even viable in the marketplace of ‘big ideas,’ would end up inspiring one of our nation’s largest big ideas; The Freedman’s Bank Building.

What’s really funny to me today, upon reflection, is remembering that my editor Neal Maillet, and the founder of the publishing house, Steven Piersanti, were both focused not on the economics of the book, but a simple and singular hope: a big public policy book that would have impact. Well, impact we have, if maybe a little different than they planned.

What’s that great saying, ‘if you want to make God laugh, tell Him your plan.’

John Hope Bryant